Having just finished the school year and officially launched my novel, Finding the Way: A Novel of Lao Tzu, I desperately needed an escape and digital detox. For ten months I micro-planned and dreamed of solitude high in the Andes. This would be my Eat, Play, Trek. However, this seclusion would be compromised with an added dimension–a trekking companion, Marc Brown. Both of us are cut from the same cloth as core soloists, lone wolf travellers who jealously guard the immersive experience without having to share it. It’s also how the writer in me does some of my best thinking. I quickly discovered he likes to talk, and he likes to whistle. A lot. I also hoped he didn’t smell, as we’d be sharing a tent for up to ten days. (Full disclosure: skanky body odour triggers a near-gag reflex in me. I could never join the army or a gym). We would be Felix and Oscar with trekking poles.

Machu Picchu is to Peru, what the Eiffel Tower is to Paris. It’s defining, it’s stunning, and it’s evocative eye candy. Some even believe it’s an energy and spiritual vortex. Sure Peru is also an emerging foodie haven as it benefits from ocean, jungle and highland food bounties, with strong Asian influences (10,000 Chinese restaurants alone in Lima, I can point out 2 awful ones). But having seen Machu Picchu almost 20 years ago, before it became a tourist gouging, cattle drive, I want to believe it still deserves to be on every bucket list. Which is why half-day trippers start lining up for the bus at 3 a.m. Which is why we gave it a miss this time.

For us, the draws were the lesser known five day treks Ausanagate (Oh-sawn-a-got-tay) and Choquequirao (cho-kay-kee-raw). The Choquequirao ruins are everything Machu Picchu is: remote, mysterious, undiscovered except it is really hard work to get to. Really hard work. Like four days of knee and lung busting ascents and descents. The holy mountain Ausanagate would be cold, uber-isolated with thin air at nearly 17,000 feet.

Lima

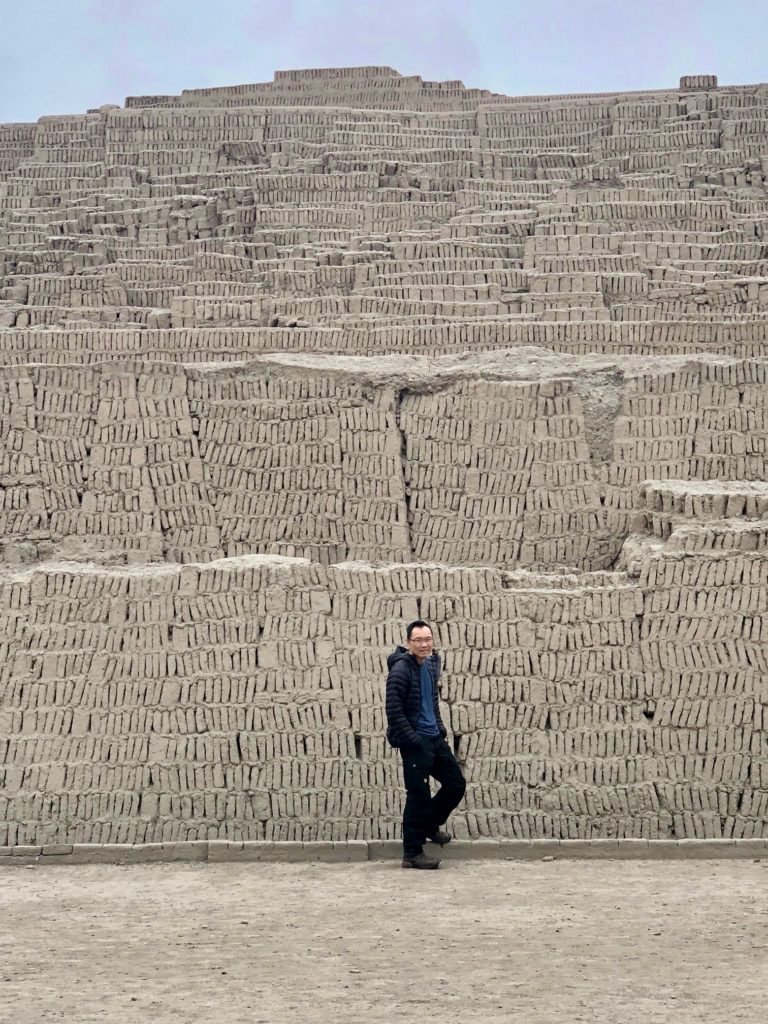

To get to these trails, all flights lead through an overnight in the hole commonly called, Lima. Except for the catacombs beneath the convent, and the pyramid in the middle of a posh Lima neighbourhood, Lima is best seen through a rear-view mirror.

Cusco

Second leg goes through Cusco—the ancient Incan capital. Despite it seemingly existing to extract western dollars from the hordes of tourists, it’s still one of Trish and my favourite travel towns. Even the master cynic Marc would agree, the indigenous/Spanish historical and cultural mix gives the town a great vibe and aesthetic.

In 1533, one-hundred and eighty sweaty, bearded, disease carrying Spanish conquistadors with local allies massacred the Incas and their empire. They would then go on to make it their own and still boast one of the most impressive people watching plazas in the world, Plaza des Armas.

Cachora

But the real prizes for us were the two treks. For months we trained, researched and talked about nothing else. To reach the trailhead for Choquequirao from Cusco, one must endure a four hour combination of a collectivo (mini-van for human sardines) and then a wreck on wheels posing as a shared taxi NASCARing along barf friendly hairpin, mountain roads to Cachora. Cachora is the launch pad for the trek and some savoury smelling mystery street meat on a stick. Marc has never ever had food or water poisoning on a travel, so he jumps on it, indifferent to the mangy dogs circling us, the lack of hygiene, the potential for salmonella, bovine or e-coli…I could go on. Much of South America is a no-meat wasted zone, as offal is viewed as a delicacy. We would later come across bull testicles (we gave the boys a miss), alpaca tenderloin (Marc said it was delish), and of course guinea pig (aka cuy) which is a lot of work picking around the itty bitty bones for little return. Too afraid that Marc would see me as a wuss, I ordered a skewer. We would later learn that they were antichuchos–beef hearts. They were absolutely yummy, so we ordered seconds.

Other than mystery meat (which may have been my ultimate undoing—more later), the only real risks were physical. I didn’t tell Marc or our wives that a few years back, remnants of the heavily armed Shining Path guerrillas robbed some American and German tourists on the trail. No one was hurt and the guerrillas haven’t been seen since.

Choquequirao

From Cachora we cabbed it to the trailhead, saving 10 monotonous kilometres. Once there, it’s clear you’ve reached the top of the Apurimac Canyon, supposedly twice as deep and punishing as the Grand Canyon. Having now done both, I’d say it’s not twice as deep, but perhaps twice as gruelling. It’s a young person’s trek. The majority of hikers are in their 20’s, too poor and heroic to hire a donkey and a handler to haul their heavy packs as we had done. Marc is staving off 70yrs of foolishness in the near horizon, and me pushing 60. Saner oldies would be binging on Netflix in golf shirts and chest high pants.

Clouds followed us during several hours of climbing, but the thorny cacti were replaced by high altitude jungle. We reached a quiet campsite and found a couple of young Frenchmen sprawled out. They had plans to do a nine day trek to Machu Picchu with their 30 kg packs. It might have been nine days since they last showered, as they reminded me of sweat infused hockey equipment. I had hoped Marc didn’t reek and tried to role model cleanliness with body wipe downs and hand sanitizing. He doesn’t sanitize. He touches anything and everything, has an iron gut, drinks the local water, takes great pictures off his iPhone (some of these are his) while I lug a DSLR, and he sleeps through anything. It is a gift. Except for his galling unwillingness to haggle, he was built for off road travel .

A dehydrated pad thai dinner caps off a gratifying day that saw us complete the first of ten days of trekking. The following morning we continued our unforgiving ascent into the clouds, grateful that I’d done months of squats and various other stupid, mindless exercises. And there it was, Choquequirao. At first we could only see the nose bleed-inducing vertical stone terraces. Having marvelled at terrace farming in other countries, there’s something brilliant about Incan agricultural techniques. They used stones to act as retaining walls in this harsh climate, but the stones also held the heat of the sun, which in turn warmed the soil. Fricken smart, eh?

We make camp just outside the ruins, only to discover that our dream of having them to ourselves was misguided. Several guided, all-inclusive groups set up near us, as do the smelly Frenchmen, and a couple of portenos (Buenos Airens) who couldn’t stop talking loudly to anybody who’d listen.

Darkening skies portended rain. Exhausted yet also excited, we hiked up the final two kilometres to the sprawling ruins. At three times the size of Machu Picchu, but only 30% excavated, we knew we only had time and energy to poke around the most accessible and easy to find sections.

Up close the ruins don’t appear anywhere near as impressive as the heavily excavated and gentrified, but Disneyed Machu Picchu. But they are ominous in their silence, and every bit as mysterious.

After Cusco fell to the Spaniards, this was supposedly one of the last bastions of Incan resistance. One can see why. It’s considerably higher and more inaccessible than Machu Picchu.

We poke around the upper plaza where funereal clouds drift in and out, adding to the stark emptiness and quietude. The park guardian said up to twenty people make it into the ruins each day. However we never saw enough to fill a minivan. There is no signage or description of the ruins, no tours, no roped off areas, no evidence of human interest. Just us and we had free rein to wander, climb and scamper over the stones, something strictly forbidden at Machu Picchu.

We settle back into our camp site. I inhale a rehydrated beef stir fry, Marc does his Knorr Swiss and vacuumed fish—the same thing he has every night….sigh. By six it’s dark and cold and everybody is huddled in their tents. Marc in particular, for all his travel invincibility, cold is his kryptonite. I wondered how he’d manage the sub zero camps at Ausangate. Though I had come down with significant flatulence which he never complained about, I continued to role model good body care and hygiene and moisturize myself. He doesn’t moisturize. He never has. How is this possible, I ask myself? In fact he only applies sunscreen to his nose.

An overnight rain wallops the area. It’s winter but the whole region is wetter and colder than it should be. I gingerly ease out of our tent into patches of mud. Some of our gear gets wet, we’re cold and feeling pissed that we’ve seen nothing but cloud for days. Marc has been up for some time, and has made hot water. He bitches about the cold but is otherwise his usual, laissez-faire self. Sometimes I hate him.

I slip on the mud and take a hard fall on my head. Dazed but miraculously I’m unscathed—a gift from the Incan Gods, perhaps. This strengthens my resolve. I have two treks to complete, anything less is unacceptable. We’re both stiff and sore, but also like a couple of teenagers ready to go to the mall, or in this case, back to the ruins.

The famous white llama terraces reflect not only the architectural and aesthetic brilliance of the Incas, but their dependence on the llamas.

The sun finally comes out and bathes the ruins in warm splendour. I stretch out and nap on the terraces by the white llamas, while Marc returns to the main plaza. I stare down into the valley. It is a glorious moment of peace and aloneness.

I return to the main plaza and we bake under the heat before poking around the highest sets of buildings that might have been warehouses and priest dwellings. There are a few more people than yesterday, but still not enough to fill a van.

Some day this may change as the regional government has proposed building a cable car that will span the canyon, allowing tourists to bypass the gruelling two day hike in 15 minutes. It will alleviate some of the tourist crush at Machu Picchu, but also destroy one of the last, great adventure treks. It’s not often one can find intimacy among the ancients. I’m reminded of the sprawling Angkor Wat which can offer similar unbridled solitude. And then there was the Pyramid of Giza where a guard who for a ‘special price,’ offered to allow me to climb the Great Pyramid after hours.

We leave the ruins and return to the camp site, which is quiet except for some porters setting up for several incoming small groups. I should’ve felt triumphant having just done Choquequirao. But I was too immersed with the challenges ahead to appreciate the moment. We have time to chill and dry out our tent and clothes. Marc boils water in our only pot, then takes it into the tent. He mumbles something about washing up. In our cooking pot. I’m not sure if I should be cursing or praising the Incan Gods.

With three days done and the long hike to Cachora ahead of us, we’re very business-like. Six or seven hours gets us to a camp site where we dry off our tent and clothes.

Bailing in Cusco

Our return to Cusco is rewarded with the glory of a hot shower and a meal that doesn’t have to be re-hydrated. Over the next few days we do laundry, re-organize our gear in prep for Ausanagate, and we eat and eat. We feel great, cocky and confident. Our legs are steel girders ready for any mountain. Only I soon start to feel weak. I’m unable to sleep, my stomach is in knots, I flirt with nausea, and I’ve lost all appetite (which is like Trump forgetting to tweet—it’s just unfathomable).

The day before we’re due to head east to Ausangate, I see the hotel ‘doctor”. He says I have mild altitude sickness. He’s young and affable, but has no credentials, so I consult another doctor in a clinic. He says I have indigestion but otherwise am good to climb, as long as I carry a thermos of hot liquids for my tummy. I think he’s a quack. But I know I’m not well enough to tackle Ausangate. So I pull the plug. I bail. I fold. And I feel like a loser. I urge Marc to go ahead. Nope he says. One for all, all for one. I’m not sure I would’ve been so loyal if the roles were reversed. I suggest we regroup and head to a lower altitude in Peru. Nope. He’s ready to head home to attend to his wife Linda’s health. Turns out it was the right call for her, and for us.

And so for the first time ever on the road, I leave early. It feels like I scored in my own net, or I’ve misspelled ‘cat’ at a spelling bee. The taste of failure. Instead of revelling in hiking Choquequirao, I couldn’t get past the quit and hid my disappointment from Marc who’d already begun re-focusing on his wife’s health.

Days later when we’ve returned home, I also re-focused. I’d spent so much of the trip either just surviving the arduous trek or looking ahead, and not being present, becoming too singularly purposed. I forgot the golden rule of allowing the unmarked path to guide you, of accepting the journey and any disappointment as part of the quest. Hence, I had lost the Way in Peru, momentarily at least.

However, I’m pleased Marc and I passed each other’s smell test. I only hope he learns to sanitize before our next trek.