Ricepaper Magazine helps bring Wayne home with this in-depth interview – stripped down and unvarnished.

“Ricepaper Magazine is a Vancouver-based Canadian magazine which has showcased Asian Canadian literature, culture, and the arts since 1994.”

The interview is reproduced below from Ricepaper Magazine.

—

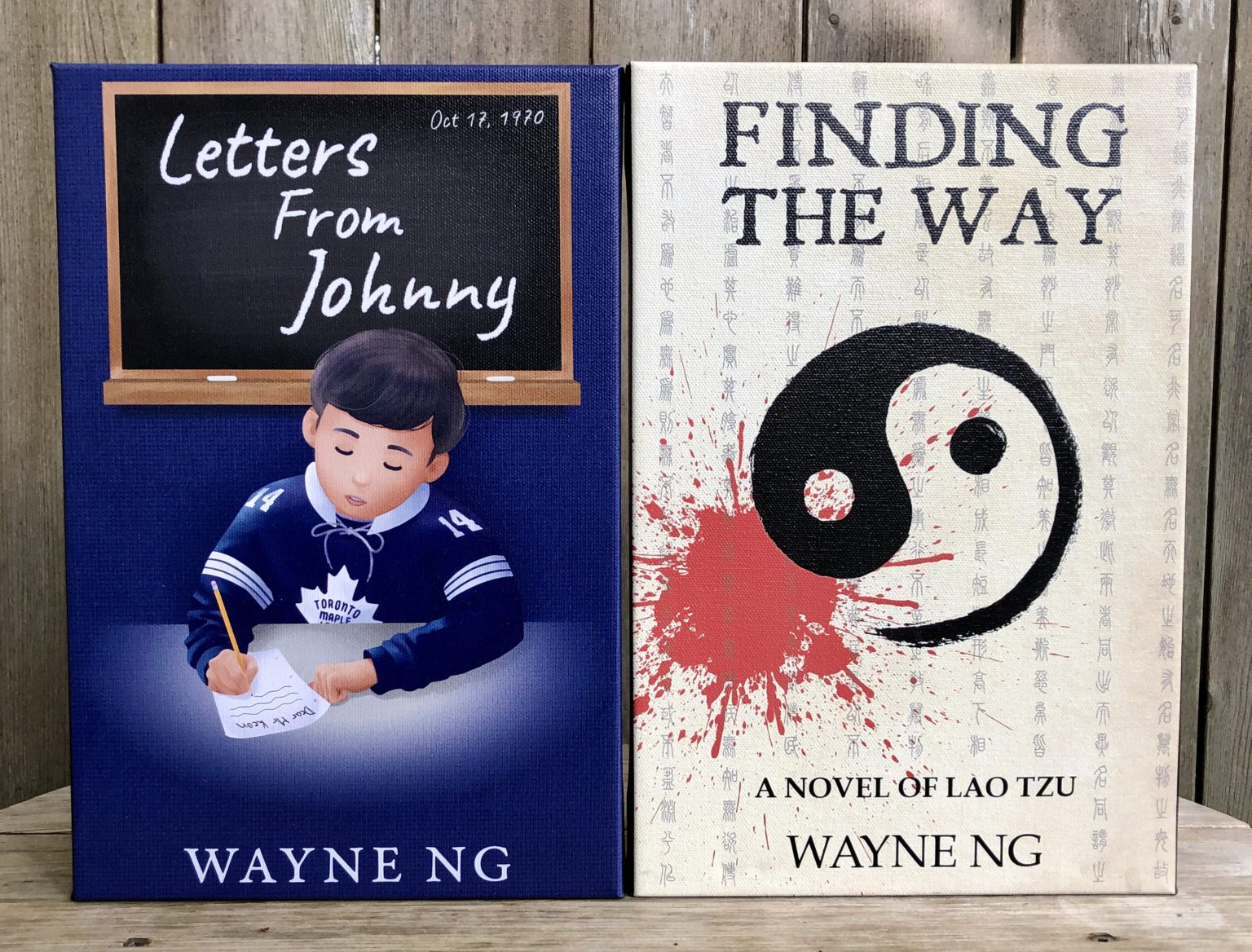

Interview with Wayne Ng, author of “Finding the Way” and “Letters from Johnny” – March 9, 2021

Wayne Ng was born in downtown Toronto to Chinese immigrants who fed him a steady diet of bitter melons and kung fu movies. Ng works as a school social worker in Ottawa but lives to write, travel, eat and play, preferably all at the same time. He is an award-winning short story and travel writer who continues to push his boundaries from the Arctic to the Antarctic, blogging and photographing along the way at WayneNgWrites.com. With the release of his latest book Letters from Johnny, Ricepaper caught up with the Ottawa-writer for an exclusive interview.

Ricepaper: Your two books are quite different from each other. How did you go from Finding the Way: A Novel of Lao Tzu, a historical fiction novel set in ancient China, to Letters From Johnny, a young adult novel set in Toronto?

For sure Finding the Way and Letters from Johnny are millennia apart in every possible way. However, they’re both fiction and self-discovery stories where the Chinese protagonists see the world with doe-eyed wonderment, only to be crushed, and then have to pick themselves up again.

Each story is a waypoint in my progression as a writer while reclaiming my roots and finding the safety to express it publicly. Many Chinese have Taoist influences in their lives, in their culture, certainly in our history. While it might seem remote nowadays, I re-discovered the essence of Taoism when I was smitten with the notion of the legendary Lao Tzu atop a water buffalo, meandering into the sunset to die. Turns out we really know little about him, so I had a blank slate to work with. Yet Lao Tzu came alive for me and was easy to write. The offshoot of that was learning about Taoism at a point in my life that was hungry for the balance and acceptance of life, which the philosophy espouses.

Letters from Johnny, however, started off as an award-winning short story many years ago. It remained dormant until FTW came out. Suddenly, I had cred. Similarly to Lao Tzu, Johnny wrote itself as though my less than idyllic childhood had to be expunged through an avatar.

Although it’s an eleven-year-old’s POV, it’s perhaps more an adult fiction offering than YA. Readers of history, off-beat immigrant stories, sports fans, and nostalgia nuts will be charmed.

Ricepaper: There’s a lot of your own story in this book. Can you tell us more about not only the story, but the characters in Letters From Johnny?

Johnny Wong is the bright, innocent but reckless, and attentionally challenged eleven-year-old I once was. He’s on the cusp of the normative psychosis of adolescence, yet still anchored in childhood. He lives with his mother, his father having left for reasons unknown to him. His only friend is an American draft dodger who rents beside them in their downtown Toronto rooming house.

Meany Ming, an elderly Chinese woman living next door is murdered. Johnny suspects it’s another neighbour, the Catwoman. Johnny is betrayed, then blackmailed by the killer, and if that wasn’t enough, the child welfare authorities threaten to separate him from his mother. Just as his world spins out of control, the FLQ crisis erupts, sending the country into a frenzy. The only solace he can find are letters to his hero, Dave Keon, because “as Captain of the Toronto Maple Leafs, (he) can be trusted.” Johnny’s coming of age parallels Canada’s when it was still very innocent and naïve, and just starting to open its doors and eyes to the world.

Although Letters from Johnnyis a work of fiction, I drew upon many childhood experiences. Just about all the characters are derivatives of people in my old hood. I went to Orde Street Public School, which was stocked predominantly with Chinese students. Draft dodgers partied down the street. The Catwoman and Meany Ming were real oddities on our street. My hippie-dippie teacher talked endlessly about Pierre Trudeau. My dad worked at the venerable Lichee Garden. News of the FLQ penetrated my insular world, and Hockey Night in Canada was the one thing other than food that brought us together.

Ricepaper: Why did you choose Dave Keon? What’s your personal connection to him? What team did you watch growing up and how about now?

I worshipped Dave Keon and the Toronto Maple Leafs. I even tried writing to him, but the lack of a stamp and return address might’ve had something to do with him not getting back to me.

Every boy looks for someone to look up to… Spiderman, cops, and celebrities are obvious ones outside of the family. Back then, a fatherless boy, like Johnny, couldn’t find a bigger hero than Dave Keon. Keon’s not a character per se, but he’s a looming presence who gives Johnny a moral foundation, a father figure, and certainty an escape after an odious betrayal.

Novels by Wayne Ng

Ricepaper: You blog about your travels. Can you share with us one of your most memorable travel stories?

Can I share two?

To be honest, I’m addicted to the great highs and wicked lows of travel.

For example, until I’d won a writing prize of boat passage to the Antarctic, I’d always been a culture vulture–suffocating crowds, chaos, and dodgy street food were my jam. But the quiet stillness of the icy continent, the complete absence of modernity, and the enormity of the icebergs–there was one three kilometres long, it all made me feel so small.

Then there was India, a mecca for solo adventuring. It’d been on my radar for many years. By the time I’d got there, I’d already travelled for months, including Myanmar, which just about wiped me out. But I was cocky and misguided. I landed in Kerala, one of the more laid-back states, yet still believing that going local and staying in $15 ‘hotels’ was essential to an authentic journey. However, the heat, the pollution, the cacophony of noise, the crowds, having to be alert and on all the time overwhelmed me. Even after several location changes, I couldn’t re-charge. I totally lost my mojo, felt depressed, lonely, and anxious. After three weeks, I did something I have never done before or since. I waved the white flag and headed home early with my tail between my legs. I was humbled, beat down, but also more self-aware and tuned in than ever before. But now I can’t wait to go back. Damned COVID.

Ricepaper: What is it like working as a social worker and writing at the same time?

I get to combine two passions, even if only one of them actually pays! Where writing and social work intersect is when the latter allows me into the most private, vulnerable crevices of people’s lives. It’s an absolute privilege. I get to witness so many children (and their parents) struggle to balance the alchemy of hope and innocence with the inevitable confusion and startling discoveries that follow. It’s given me insight and clarity into how and why people are who they are. It’s definitely informed my character development.

My third novel which is seeking publication is about a messy and dysfunctional yet hypnotic trainwreck of a family, drawn heavily from my decades of social work experience. The principal characters are once again, composites of people who touched me with their courageous lives and authentic stories.

Ricepaper: Do you have any strategies on setting your writing schedule and process to share with writers?

I’d like to tell you that I have a very structured, methodical, and regimented writing schedule but that’d be a lie. My craft is structured around my day job. However, if I’m onto something, I’ll inhabit the project. I’ll write first thing in the morning, in between clients, over lunch, evenings, weekends… it’ll overtake my life until it’s expunged or in submittable form. It’s an intense and thrilling ride that I miss when I’m not writing.

I would tell other writers to marry a librarian who understands their writing obsession and the power and importance of reading. Seriously, I’d say write about what moves them and ensure that they are totally passionate about it. Case in point, I had started on a sequel to my first novel about the development of Sun Tzu’s Art of War. But it didn’t speak to me, it was laborious, I had no juice and the writing inevitably showed. So I put it down, for now – maybe one day it will excite me but not now – trust your gut.

I have also found it helpful to do things related to writing: I listen to writing podcasts while I’m exercising, read about the craft and industry, read for pleasure in genres that I want to focus on, re-work old stories and submit them for publication.

Ricepaper: How did you find your current publishers? Did you find them or did they find you?

Alice Poon who used to curate for Earnshaw Books discovered me online when I was hunting for an agent. God bless, Alice, an accomplished Chinese historical fiction writer herself.

Guernica Editions was one of a number of small indie publishers I queried for LFJ. I was fortunate that Michael Mirolla, the eternal gentleman, saw something in a lonely eleven-year-old boy with punctuation problems.

Ricepaper: You dedicated Letters From Johnny to your grandfather. Can you share with us more about your family history and how it’s influenced your writing?

Like many early Chinese immigrants, our family experiences of hardship were cloaked in subterfuge, left unshared, and silent. Avoidance of painful memories and experiences became a generational contagion. Subsequent kin all studied and worked hard, never rocking the boat, never asking too many questions. Even grandfather’s name was a murky ‘paper name.’

Then I stumbled onto a couple of UBC academic librarians, Allan Cho and Sarah Zhang who put together a database of Chinese immigrants to Canada between 1886-1949–a phenomenal resource. After some sleuthing, there grandfather was–in a grainy black and white photo, dated 1911 in Victoria. Devilishly handsome, with the same striking mole just above his eye that I vividly recalled fifty years later.

Like many other early settlers, he wasn’t allowed to bring his family because of the Head Tax than the Exclusion Act. Instead, he’d return home every few years, sow his seed (fathering five children), then rush back to Canada. Eventually, the laws changed and family members immigrated to Canada in dribs and drabs. Sadly, by the time grandfather was reunited with grandmother in the late 60s, he died shortly thereafter in our Henry Street rooming house.

While I dedicated the novel to him, we got our 14-year old nephew to illustrate the cover. I hope someday he recognizes how he was part of bringing our family history alive.